Command-line interface#

You can use Tax-Calculator on your own computer via a command-line

interface (CLI) called tc. This approach requires the use of a text

editor to prepare simple files that are read by tc. Computer

programming knowledge is not required, but this approach to using

Tax-Calculator assumes you are willing to work at the command line

(Terminal on Mac or Anaconda Prompt on Windows) and to use a text

editor (for example, TextEdit on Mac or Notepad on Windows).

Test tc CLI#

The tc CLI is part of the Tax-Calculator taxcalc package you

installed on your computer as part of Getting started.

To check your installation of tc, enter the following command:

% tc --test

Expected output (after several seconds) is PASSED TEST. If you get

FAILED TEST, something went wrong in the installation process. If

the installation test fails, please report your experience by

creating a new

issue.

If your installation passes the test, you are ready to begin using

tc to analyze tax reforms. Continue reading this section for

information about how to do that. But if you want a quick hint about

the range of tc capabilities, enter the following:

% tc --help

The basic idea of tc tax analysis is that each tax reform is

specified in a text file using a simple method to describe the details

of the reform. Read the next part of this section to see how policy

reform files are formatted.

Specify tax reform#

The details of a tax reform are contained in a text file that you write with a text editor. The reform is expressed by specifying which tax policy parameters are changed from their current-law values by the reform. The current-law values of each policy parameter are documented in this section of the guide. The timing and magnitude of these policy parameter changes are written in JSON, a simple and widely-used data-specification language.

For several examples of reform files and the general rules for writing JSON reform files, go to this page.

Specify analysis assumptions#

This part explains how to specify economic assumption files used in tax analysis. This is an advanced topic, so if you want to start out using the default assumptions (which are documented in this section) of the guide), you can skip this part now and come back to read it whenever you want to change the default assumptions. The next part of this section discusses filing-unit input files.

The details of analysis assumptions are contained in a text file that you write with a text editor. The assumptions are expressed by specifying which parameters are changed from their default values. The timing and magnitude of these parameter changes are written in JSON, a simple and widely-used data-specification language.

For examples of assumption files and the general rules for writing JSON assumption files, go to this page.

Specify behavioral responses#

For a JSON file template that can be used to specify you own values of each response elasticity, go to this page.

Specify filing units#

The taxcalc package containing tc does not include an

IRS-SOI-PUF-derived microsimulation sample. This is because, unlike

Census public-use files, the IRS-SOI Public Use File is

proprietary. If you or your organization has paid IRS to use the PUF

version being by Tax-Calculator, then it may be possible for us to

share with you one of our PUF-derived samples: the 2011-based puf.csv

or the 2015-based tmd.csv, which are described in Data for Tax-Calculator.

Otherwise, you have two choices.

First, you can easily create with a text editor a CSV-formatted

file containing several filing units whose experience under your tax

reform is of interest to you. Much of the public discussion of tax

reforms is of this type: how is this family or that family affected by

a reform; how do they fare under different reforms; etc. The test

conducted to check the tc installation has left one such file. It is

called test.csv and contains two filing units: a lower income family

and a higher income family. You can use this test.csv file as tc

input to analyze your tax reforms. Before creating your own input

files be sure to read the short set of guidelines that appear after

this list of two choices. Some people pursue this approach using a

statistical pacakge like R or Stata, in which case the tc CLI

program can be invoked from within the statistical package. There may

be a need (especially on Windows) to add to the system

PATH

in order to do this.

Second, the taxcalc does include a freely available

microsimulation sample containing only filing units derived from a

recent March CPS survey. For several reasons, the results generated by

this cps.csv file are substantially different from the results

generated by the puf.csv or tmd.csv files. The cps.csv file

contains a sample of the population while the puf.csv and tmd.csv

files contain mostly a sample of income tax filers in which

high-income filing units are over represented. Also, the cps.csv

file has many income variables that are missing (and assumed to be

zero by Tax-Calculator), which causes an understating of total

incomes, especially for those with high incomes. All these differences

mean that the aggregate revenue and distributional results generated

when using the cps.csv file as input to Tax-Calculator can be

substantially different from the results generated when using the

puf.csv or tmd.csv file as input. And this is particularly true

when analyzing reforms that change the tax treatment of high-income

filers.

Input-File-Preparation Guidelines

The tc CLI to Tax-Calculator is flexible enough to read almost any

kind of CSV-formatted input data on filing units as long as the

variable names correspond to those expected by Tax-Calculator. The

only required input variables are RECID (a unique filing-unit record

identifier) and MARS (a positive-valued filing-status

indicator). Other variables in the input file must have variable names

that are listed in the Input

Variables

section for them to affect the tax calculations. Any variable listed

in Input Variables that is not in an input file is automatically set

to zero for every filing unit. Variables in the input file that are

not listed in Input Variables are ignored by Tax-Calculator.

However, there are important data-preparation issues related to the

fact that the payroll tax is a tax on individuals, not on income-tax

filing units. Tax-Calculator expects that the filing-unit total for

each of several earnings-related variables is split between the

taxpayer and the spouse. It is the responsibility of anyone preparing

data for Tax-Calculator input to do this earnings splitting. Here are

the relationships between the filing-unit variable and the taxpayer

(p) and spouse (s) variables expected by Tax-Calculator:

e00200 = e00200p + e00200s

e00900 = e00900p + e00900s

e02100 = e02100p + e02100s

Obviously, when MARS is not equal to 2 (married filing jointly), the

values of the three s variables are zero and the value of each p

variable is equal to the value of its corresponding filing-unit

variable. Note that the input file can omit any one, or all, of these

three sets variables. If the three variables in one of these sets are

omitted, the required relationship will be satisfied because zero

equals zero plus zero.

In addition to this earnings-splitting data-preparation issue,

Tax-Calculator expects that the value of ordinary dividends (e00600)

will be no less than the value of qualified dividends (e00650) for

each filing unit. And it also expects that the value of total pension

and annuity income (e01500) will be no less than the value of

taxable pension and annuity income (e01700) for each filing

unit. Tax-Calculator also expects the value of the required MARS

variable to be in the range from one to five, and the value of the EIC

variable to be in the range from zero to three. Again, it is your

responsibility to prepare input data for Tax-Calculator in a way that

ensures these relationships are true for each filing unit.

Here’s an example of how to specify a few stylized filing units with and without young children:

RECID,MARS,XTOT,EIC,n24,...

11 , 1 , 1 , 0 , 0 ,... <== single person with no kids

12 , 4 , 2 , 1 , 1 ,... <== single person with a young kid

13 , 2 , 4 , 2 , 2 ,... <== married couple with two young kids

Be sure to read the documentation of the MARS, XTOT, EIC, and

n24 input variables. Also, there may be a need to add other

child-age input variables if you want to simulate reforms like a child

credit bonus for young children. Also, the universal basic income

(UBI) reform is implemented using its own set of three age-group-count

input variables.

The name of your input data file is also relevant to how tc will

behave. If your file name ends with cps.csv, puf.csv or tmd.csv,

tc will automatically extrapolate your data from its base year to

the year you specify for tax calculations to be calculated using built

in growth factors, extrapolated weights, and other adjustment

factors. If you are not using the cps.csv, puf.csv, or tmd.csv

input, it is likely that your data will not be compatible with these

extrapolations and you should adopt filenames with alternative

endings.

Initiate reform analysis#

Executing tc requires at least three command-line arguments: the

name of an input file containing one or more filing units, the year

for which the tax calculations are done, and an option specifying what

kind of output is to be generated. A baseline policy file is

optional; specifying no baseline file implies the baseline policy is

current-law policy. A policy reform file is optional; specifying no

reform file implies calculations are done for the baseline policy. An

economic assumption file is also optional; no assumption file implies

you want to use the default values of the assumption parameters. The

output files written by tc are built-up from the name of the input

file, tax year, baseline file, reform file, and assumption file using

a # character if an option is not specified.

Here we explain how to conduct tax analysis with tc by presenting a

series of examples and explaining what output is produced in each

example. There are several types of output that tc can generate so

there will be more than a few examples. All the examples assume that

the input file is the built-in cps.csv data sample and are conducted

on an old Mac with a slow Intel CPU chip.

% tc cps.csv 2020 --dumpdb

Read input data for 2014; input data were extrapolated to 2020

Write dump output to sqlite3 database file cps-20-#-#-#-#.db

Execution time is 9.6 seconds

The dump database contains 2020 income tax liabilities for each filing

unit under both baseline and reform policy regimes. The name of the

dump database file is cps-20-#-#-#-#.db. Because we did not use the

--dumpvars option, a minimal set of baseline/reform variables are

included in the dump database.

The main advantage of the SQLite3 database is that the Anaconda Python distribution includes sqlite3 (or sqlite3.exe on Windows), a command-line tool that can be used to tabulate dump output using structured query language (SQL). SQL is a language that you use to specify the tabulation you want and the SQL database figures out the procedure for generating your tabulation and then executes that procedure; there is no computer programming involved.

To manipulate the dump database file, use the SQLite command-line

program (called sqlite3.exe on Windows or sqlite3 on other

operating systems), which is automatically installed as part of the

Anaconda Python distribution. Full sqlite3 documentation is

here.

Here is a quick way to see the structure of the dump database:

% echo ".schema" | sqlite3 cps-20-#-#-#-#.db

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS "base" (

"RECID" INTEGER,

"s006" REAL,

"data_source" INTEGER,

"XTOT" INTEGER,

"MARS" INTEGER,

"expanded_income" REAL,

"income_group" INTEGER

);

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS "baseline" (

"RECID" INTEGER,

"iitax" REAL

);

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS "reform" (

"RECID" INTEGER,

"iitax" REAL

);

Notice that the dump output includes three relational database tables:

base, baseline, and reform. The base tables contains baseline

values for variables that keep the same value when policy changes.

The baseline and reform tables can contain variables in addition

to RECID and iitax if the --dumpvars option is used. For a

complete list of input variables, see the Input

Variables

section. For a complete list of output variables, see the Output

Variables

section.

There are several advantages to using a database file for dump output: the database is much smaller than the equivalent CSV-formatted files, and dump output can be tabulated using structured query language (SQL). SQL is a language that you use to specify the tabulation you want and the SQL database figures out the procedure for generating your tabulation and then executes that procedure; there is no computer programming involved. We illustrate tabulation of dump output in a subsequent section.

Next, we show how to generate tabular and graphical output for a

simple policy reform specified in the ref3.json file:

// ref3.json raises personal exemption amount to 8000 in 2022,

// after which it continues to be indexed to price inflation.

{

"II_em": {"2022": 8000}

}

To get both tabular and graphical output, and to check on the policy

reform, we execute the following commands (note that on Windows you

should replace cat with type):

% tc cps.csv 2024 --reform ref3.json --params --tables --graphs

Read input data for 2014; input data were extrapolated to 2024

Write baseline policy parameter values to file cps-24-#-ref3-#-#-params.bas

Write reform policy parameter values to file cps-24-#-ref3-#-#-params.ref

Write tabular output to file cps-24-#-ref3-#-#-tables.text

Write graphical output to file cps-24-#-ref3-#-#-pch.html

Write graphical output to file cps-24-#-ref3-#-#-atr.html

Write graphical output to file cps-24-#-ref3-#-#-mtr.html

% diff cps-24-#-ref3-#-#-params.bas cps-24-#-ref3-#-#-params.ref

34c34

< II_em 0.0

---

> II_em 9059.7

% cat cps-24-#-ref3-#-#-tables.text

Weighted Tax Reform Totals by Baseline Expanded-Income Decile

Returns ExpInc IncTax PayTax LSTax AllTax

(#m) ($b) ($b) ($b) ($b) ($b)

0 21.49 46.8 -1.0 3.6 0.0 2.6

1 21.49 371.0 -11.5 31.8 0.0 20.4

2 21.49 696.8 -12.3 49.9 0.0 37.6

3 21.49 934.8 -1.9 55.4 0.0 53.5

4 21.49 1177.8 4.8 78.4 0.0 83.2

5 21.49 1486.0 15.3 105.4 0.0 120.6

6 21.49 1893.5 32.0 136.6 0.0 168.7

7 21.49 2465.2 74.8 194.6 0.0 269.4

8 21.49 3392.4 176.0 295.6 0.0 471.6

9 21.49 8037.6 1313.1 558.6 0.0 1871.7

A 214.88 20502.0 1589.2 1510.0 0.0 3099.2

Weighted Tax Differences by Baseline Expanded-Income Decile

Returns ExpInc IncTax PayTax LSTax AllTax

(#m) ($b) ($b) ($b) ($b) ($b)

0 21.49 46.8 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

1 21.49 371.0 -2.1 0.0 0.0 -2.1

2 21.49 696.8 -8.3 0.0 0.0 -8.3

3 21.49 934.8 -10.0 0.0 0.0 -10.0

4 21.49 1177.8 -14.5 0.0 0.0 -14.5

5 21.49 1486.0 -22.4 0.0 0.0 -22.4

6 21.49 1893.5 -33.0 0.0 0.0 -33.0

7 21.49 2465.2 -45.0 0.0 0.0 -45.0

8 21.49 3392.4 -74.3 0.0 0.0 -74.3

9 21.49 8037.6 -121.7 0.0 0.0 -121.7

A 214.88 20502.0 -331.1 0.0 0.0 -331.1

The graphs in the three .html files can be viewed in your browser.

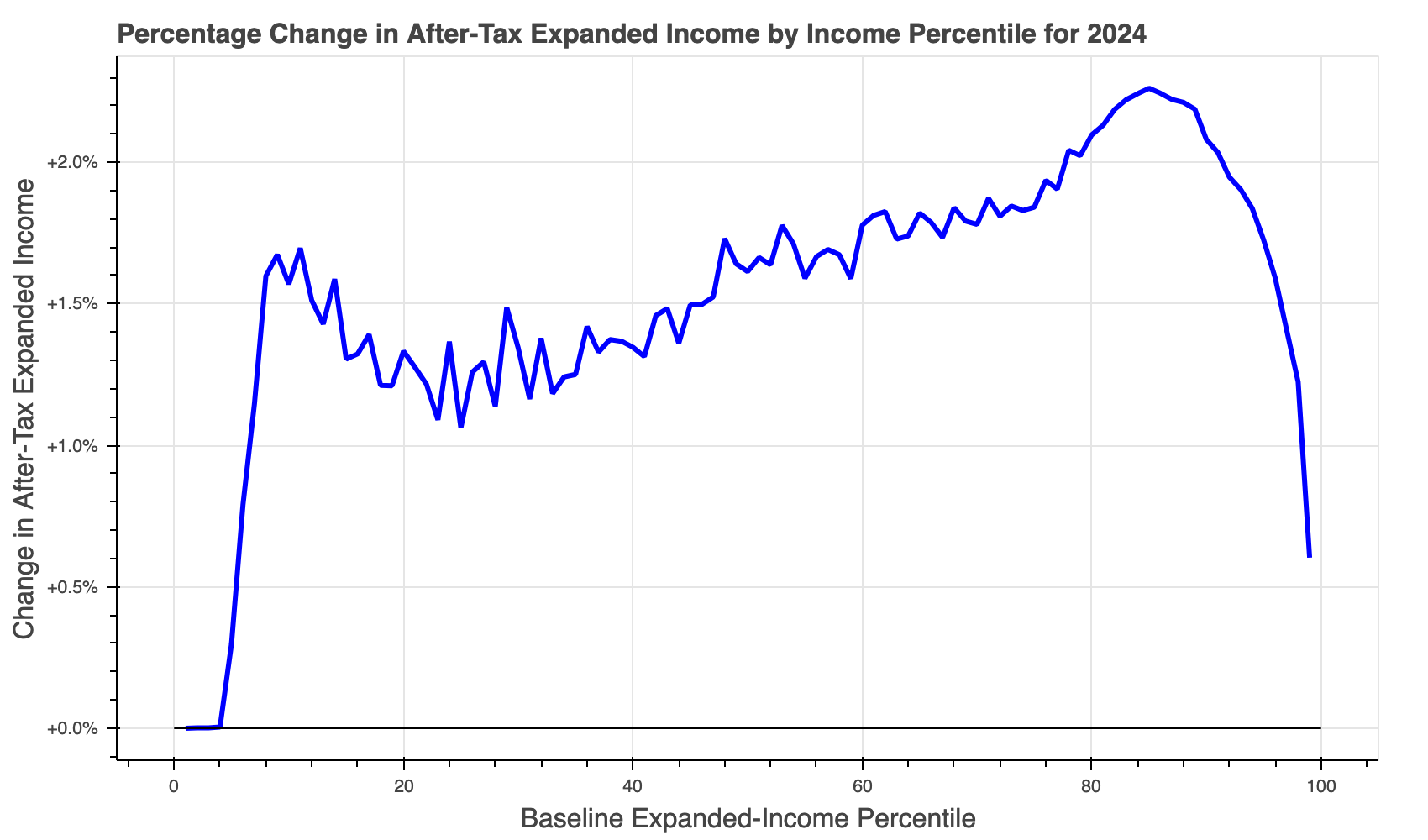

The cps-24-#-ref3-#-#-pch.html file looks something like this:

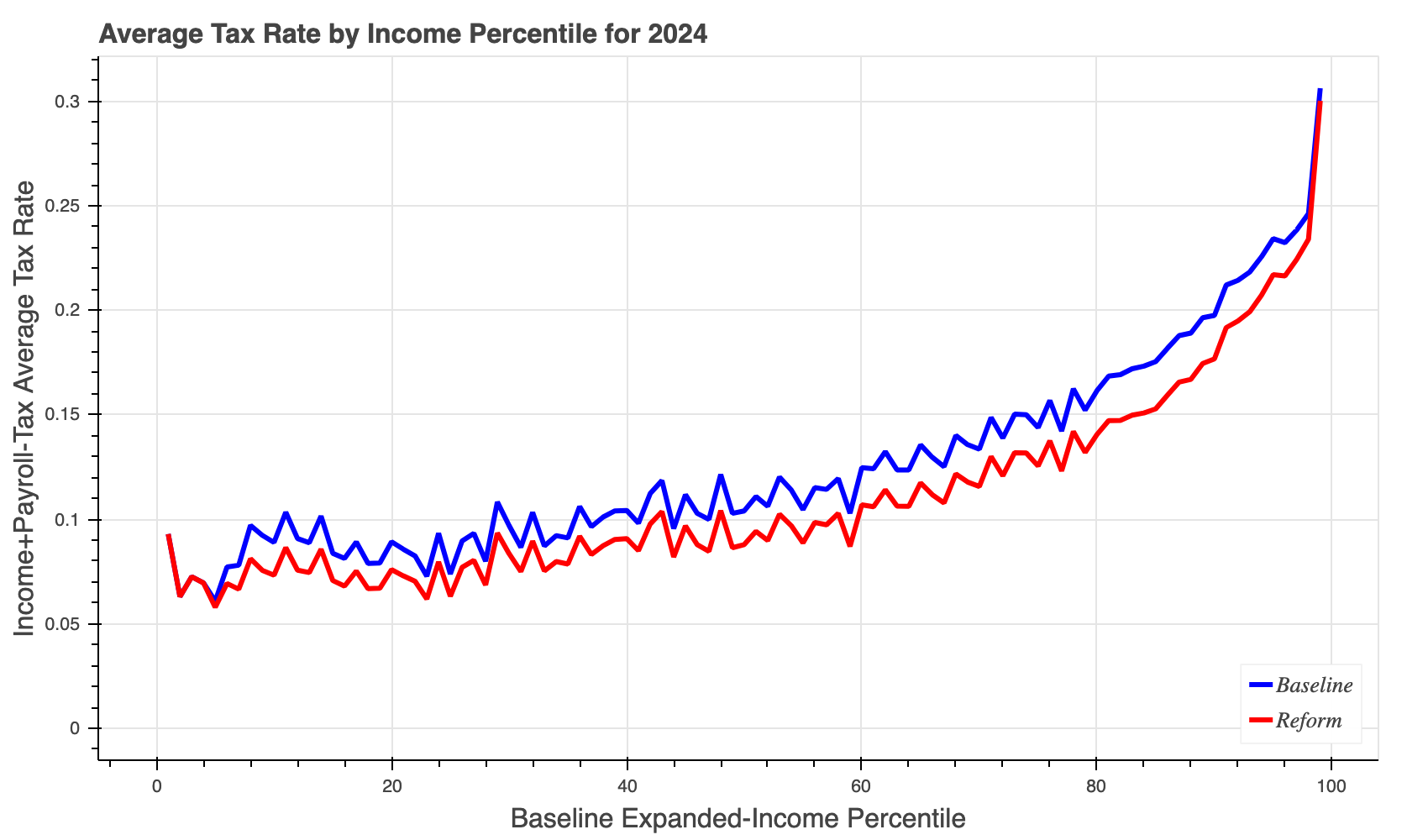

The cps-24-#-ref3-#-#-atr.html file looks something like this:

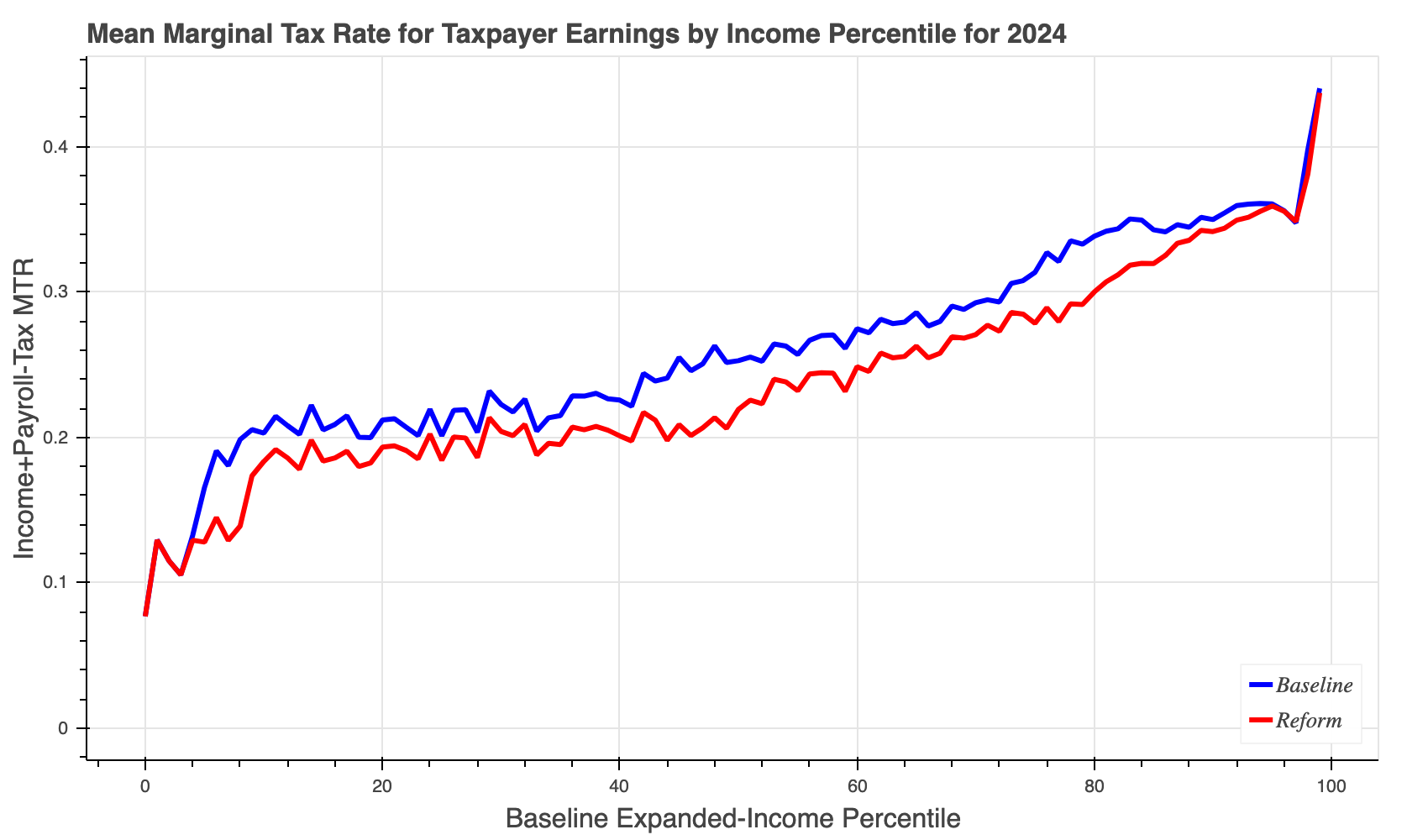

The cps-24-#-ref3-#-#-mtr.html file looks something like this:

In all the examples in this section, we have executed one tc run at

at time. But what if you want to execute many tc runs because

you want results for many years and/or for several different reforms.

The best way to execute multiple-year runs (say, ten-year runs to

generate budget-window estimates) is to use the --numyears N option

as decribed

here

and below in the final section of this document.

Tabulate reform results#

Given the prevalence of

SQLite, tc dump output can be tabulated using a wide range of

statistical software tools. For example, a dump database file

can be directly manipulated in R or Python.

Here we give some examples of using the sqlite3 command-line program

that is part of the Anaconda distribution (so it is always available

when using Tax-Calculator). The first step, of course, is to use the

--dumpdb option when running tc. Then you can use the sqlite3

tool interactively or use it to execute SQL scripts you have saved in

a text file. We’ll provide examples of both those approaches. There

are many online tutorials on the SQL select command; if you want to

learn more, search the Internet.

First, we provide a simple example of using sqlite3 interactively.

This approach is ideal for exploratory data analysis. Our example

uses the cps.csv file as input, but you can do the following with

the output from any input file that has weights (s006). Also, we

specify no policy reform file, so the output is for current-law

policy. What you cannot see from the following record of the analysis

is that the sqlite3 tool keeps a command history, so pressing the

up-arrow key will bring up the prior command for editing. This

feature reduces substantially the amount of typing required to conduct

exploratory data analysis.

% tc cps.csv 2024 --reform ref3.json --dumpdb

Read input data for 2014; input data were extrapolated to 2024

Write dump output to sqlite3 database file cps-24-#-ref3-#-#.db

Execution time is 35.6 seconds

% sqlite3 cps-24-#-ref3-#-#.db

SQLite version 3.39.5 2022-10-14 20:58:05

Enter ".help" for usage hints.

sqlite> YOUR FIRST SQL COMMAND GOES HERE

sqlite> YOUR SECOND SQL COMMAND GOES HERE

sqlite> ...

sqlite> YOUR FINAL SQL COMMAND GOES HERE

sqlite> .quit

Second, we provide a simple example of using sqlite3 with SQL

commands stored in a text file. This approach is useful if you want

to tabulate many different output files in the same way. This second

example assumes that the first example has already been done.

% cat tab.sql

.mode column

.print *** unweighted and weighted tax unit counts:

SELECT

COUNT(*) AS raw_count, -- unweighted count of tax units (#)

ROUND(SUM(s006)*1e-6, 3) AS wgh_count -- weighted count of tax units (#M)

from base;

.print *** weighted tax unit counts by filing status (MARS):

.width 4 -9

SELECT

MARS, -- tax filing status

ROUND(SUM(s006)*1e-6, 3) AS wgh_count -- weighted count of tax units (#M)

FROM base

GROUP BY MARS;

.headers off

SELECT

'A', -- tax filing status

ROUND(SUM(s006)*1e-6, 3) AS wgh_count -- weighted count of tax units (#M)

FROM base;

.headers on

.print *** specify base.income_group

UPDATE base SET income_group =

CASE -- specify the income_group brackets as desired

WHEN expanded_income < 0.0 THEN 0

WHEN expanded_income < 50.0e3 THEN 1

WHEN expanded_income < 100.0e3 THEN 2

WHEN expanded_income < 500.0e3 THEN 3

WHEN expanded_income < 1.0e6 THEN 4

ELSE 5

END;

.print *** tabulate weighted tax units and baseline.iitax by income_group:

.width 1 -9 -9 -9 -9

SELECT

income_group AS g, -- income_group

ROUND(SUM(s006)*1e-6, 3) AS units, -- tax units (#M)

ROUND(SUM(s006*b.iitax)*1e-9, 3) AS b_iitax, -- baseline iitax ($B)

ROUND(SUM(s006*r.iitax)*1e-9, 3) AS r_iitax, -- reform iitax ($B)

ROUND(SUM(s006*(r.iitax-b.iitax))*1e-9, 3) AS r_b_diff -- reform-baseline diff

FROM base JOIN baseline AS b USING(RECID) JOIN reform AS r USING(RECID)

GROUP BY income_group;

.headers off

SELECT

'A' AS g, -- all income groups

ROUND(SUM(s006)*1e-6, 3) AS units, -- tax units (#M)

ROUND(SUM(s006*b.iitax)*1e-9, 3) AS b_iitax, -- baseline iitax ($B)

ROUND(SUM(s006*r.iitax)*1e-9, 3) AS r_iitax, -- reform iitax ($B)

ROUND(SUM(s006*(r.iitax-b.iitax))*1e-9, 3) AS r_b_diff -- reform-baseline diff

FROM base JOIN baseline AS b USING(RECID) JOIN reform AS r USING(RECID);

.headers on

Using this tab.sql script to tabulate the cps-24-#-ref3-#-#.db

database produces these results in about 1.3 seconds:

% sqlite3 cps-24-#-ref3-#-#.db < tab.sql

*** unweighted and weighted tax unit counts:

raw_count wgh_count

--------- ---------

280005 214.876

*** weighted tax unit counts by filing status (MARS):

MARS wgh_count

---- ---------

1 120.117

2 71.899

3 4.191

4 18.67

A 214.876

*** specify base.income_group

*** tabulate weighted tax units and baseline.iitax by income_group:

g units b_iitax r_iitax r_b_diff

- --------- --------- --------- ---------

0 0.105 0.0 0.0 0.0

1 88.203 -5.16 -26.722 -21.563

2 62.213 121.065 52.266 -68.798

3 61.721 1043.226 823.515 -219.711

4 1.85 261.946 247.438 -14.508

5 0.784 499.231 492.709 -6.521

A 214.876 1920.308 1589.207 -331.101

Notice the -331.101 aggregate change in income tax liability induced by the reform is essentially the same as the -331.1 amount in the –tables output above, although the income subgroups amounts differ because the income groups are defined in different ways.

Generate budget-window results#

Sometimes ten-year results for a reform are needed. The easiest way

to generate such budget-window results is to use the CLI tool’s

--numyears N option. If ext.json contains the

extend-TCJA-beyond-2025 reform, then we can execute the following run:

% tc --version

Tax-Calculator 4.6.2 on Python 3.12

% tc ../tmd.csv 2026 --numyears 10 --reform ext.json --tables

Read input data for 2021; input data were extrapolated to 2026

Write tabular output to file tmd-26-#-ext-#-#-tables.text

Advance input data and policy to 2027

Write tabular output to file tmd-27-#-ext-#-#-tables.text

Advance input data and policy to 2028

Write tabular output to file tmd-28-#-ext-#-#-tables.text

Advance input data and policy to 2029

Write tabular output to file tmd-29-#-ext-#-#-tables.text

Advance input data and policy to 2030

Write tabular output to file tmd-30-#-ext-#-#-tables.text

Advance input data and policy to 2031

Write tabular output to file tmd-31-#-ext-#-#-tables.text

Advance input data and policy to 2032

Write tabular output to file tmd-32-#-ext-#-#-tables.text

Advance input data and policy to 2033

Write tabular output to file tmd-33-#-ext-#-#-tables.text

Advance input data and policy to 2034

Write tabular output to file tmd-34-#-ext-#-#-tables.text

Advance input data and policy to 2035

Write tabular output to file tmd-35-#-ext-#-#-tables.text

PR

#2900

discusses how much faster this is relative to executing ten separate

tc runs, and also shows how to tabulate the ten-year aggregate

reform result from the files generated by this run.

Because the reform-induced change in aggregate federal income tax liability is located on the last row of each tables output file in the fourth column, we can look at the ten-year results quickly:

% tail -1 tmd-??-*tables.text

==> tmd-26-#-ext-#-#-tables.text <==

A 192.41 20828.3 -284.0 0.0 0.0 -284.0

==> tmd-27-#-ext-#-#-tables.text <==

A 193.77 21613.4 -291.7 0.0 0.0 -291.7

==> tmd-28-#-ext-#-#-tables.text <==

A 194.72 22404.7 -299.5 0.0 0.0 -299.5

==> tmd-29-#-ext-#-#-tables.text <==

A 195.66 23243.3 -291.8 0.0 0.0 -291.8

==> tmd-30-#-ext-#-#-tables.text <==

A 196.58 24115.1 -299.8 0.0 0.0 -299.8

==> tmd-31-#-ext-#-#-tables.text <==

A 197.48 25020.0 -307.8 0.0 0.0 -307.8

==> tmd-32-#-ext-#-#-tables.text <==

A 198.35 25952.7 -315.7 0.0 0.0 -315.7

==> tmd-33-#-ext-#-#-tables.text <==

A 199.21 26905.4 -323.6 0.0 0.0 -323.6

==> tmd-34-#-ext-#-#-tables.text <==

A 200.03 27878.9 -331.6 0.0 0.0 -331.6

==> tmd-35-#-ext-#-#-tables.text <==

A 200.83 28883.0 -339.6 0.0 0.0 -339.6

A simple way to sum up the ten annual changes is to use the awk

program, which

could be called gawk or gawk.exe on your computer, as follows:

% tail -1 tmd-??-*tables.text | awk '$1~/A/{n++;c+=$4}END{print n,c}'

10 -3085.1